Recording of the first day of the conference:

Recording of the second day of the conference:

1. Session Capitalism - money - labour

1. Session Capitalism - money - labour

2. Presentation of Russian Association of Political Philosophy

3. Session Marxism, feminism and problem of social reproduction

4. Final Roundtable. How to Look into the Future? A View from Russian Perspective

Derrida has famously stated that "there will be no future without Marx, without the memory and inheritance of Marx". The multiplicity of academic and popular events in the year of Marx's anniversary testifies to the truth of these words. Two hundred years after his birth, the thought of Karl Marx remains a rousing way to look at the future.

The fall of the Soviet project has effectively eliminated all major social alternatives from the current world order and impoverished the global political imagination. It is no accident that the two most recent decades have generated no utopias and in numerous polities witnessed the hegemony of nostalgic conservative projects of returning into an imagined past to become "great again." However, the dissatisfaction with the disappearance of the meaningful future is constantly growing, and Marx has now been rediscovered as a visionary who knew to see seeds of the future in the present. His books are bestsellers again on both sides of the Atlantic, where people are desperately searching for answers to the challenges of the XXI century: inequality, fundamentalism, imperial wars, and crisis of democracy.

One year after Marx's anniversary, we gather in Moscow to inquire about the future with Marx. How can Marxian thought help us imagine a better future? What is the hope that it provides today? How does Marxist imagination account for the Soviet experience and how can it operate within the societies that emerged from the Soviet past? What is the Marxist view of history today and what are the social classes capable of developing it? What do we learn from Marx after the end of classical Marxism?

The purpose of this two-day conference is to familiarize a wide public in Russia with the visions of future in contemporary Marxist and Post-Marxist thought. It is also meant to question what could be the Marist view from Russia today by bringing Russian scholars into dialogue with the leading intellectuals from other countries.

The fall of the Soviet project has effectively eliminated all major social alternatives from the current world order and impoverished the global political imagination. It is no accident that the two most recent decades have generated no utopias and in numerous polities witnessed the hegemony of nostalgic conservative projects of returning into an imagined past to become "great again." However, the dissatisfaction with the disappearance of the meaningful future is constantly growing, and Marx has now been rediscovered as a visionary who knew to see seeds of the future in the present. His books are bestsellers again on both sides of the Atlantic, where people are desperately searching for answers to the challenges of the XXI century: inequality, fundamentalism, imperial wars, and crisis of democracy.

One year after Marx's anniversary, we gather in Moscow to inquire about the future with Marx. How can Marxian thought help us imagine a better future? What is the hope that it provides today? How does Marxist imagination account for the Soviet experience and how can it operate within the societies that emerged from the Soviet past? What is the Marxist view of history today and what are the social classes capable of developing it? What do we learn from Marx after the end of classical Marxism?

The purpose of this two-day conference is to familiarize a wide public in Russia with the visions of future in contemporary Marxist and Post-Marxist thought. It is also meant to question what could be the Marist view from Russia today by bringing Russian scholars into dialogue with the leading intellectuals from other countries.

The conference will be held in WINZAVOD Contemporary Art Center (4th Syromyatnichesky lane 1/8).

All of the sessions (except 'Politics of Time' session) will be held in the Vintage hall. 'Politics of time' session will be organized in pop/off/art galery.

SPEAKERS

Cinzia Arruzza

Researcher in feminist theory and political thought of ancient Greece and Rome; Associate Professor of Philosophy at the New School, New York

Ilya Budraitskis

Historian and political theorist; Lecturer at Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences

Keti Chukhrov

Philosopher, an associate professor at the Department of Сultural Studies at the Higher School of Economics (Moscow), Marie Sklodowska Curie fellow in UK; Author of numerous texts on art theory and philosophy

Elena Gapova

Researcher in gender and social inequality studies; Associate Professor of Sociology in Western Michigan University

Jodi Dean

Political theorist; Professor in the Political Science department at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York

Angela Dimitrakaki

Researcher in feminist and marxist methodologies in art history; Senior Lecturer in Contemporary Art History and Theory University of Edinburgh

Michael Heinrich

Political theorist; Research fellow in Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft, Berlin

Maurizio Lazzarato

Sociologist and philosopher; Researcher at Pantheon-Sorbonne University (University Paris I)

Artemy Magun

Philosopher; Professor of Democratic Theory, Department of Sociology and Philosophy at European University at Saint Petersburg

Vladimir Mau

Economist; Researcher in economic policy; Rector of Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration

Valery Podoroga

Philosopher; Professor and Senior Researcher; Institute of Philosophy RAS (Moscow)

Alexei Penzin

Philosopher; Reader at the Faculty of Arts, University of Wolverhampton (UK) and Research Fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Moscow

Alexey Savin

Philosopher; Professor at Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration

Teodor Shanin

OBE; Sociologist of Peasantry; Founder and President of Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences

Marina Simakova

Researcher in social and political thought; Research fellow in Department of Sociology and Philosophy at European University at Saint Petersburg

Andrey Shevchuk

Researcher in the sociology of work; Associate Professor of Sociology in National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow

Vladislav Sofronov

Philosopher; Independent researcher

Dimitris Vardoulakis

Researcher in theories of power and sovereignty; Associate Professor in Philosophy in Western Sydney University

Greg Yudin

Philosopher and sociologist; Professor at Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences

Sergey Zuev

Cultural manager; Professor; Rector of Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME

Friday, May 24

10:00-10:30

Greetings

Rector of MSSES Sergey Zuev & organizing committee

10:30–15:00

Parallel Panels

Session 1. Marx and Contemporary Materialism

Session 2. Politics of Time

The sessions will be held in English without translation.

Session 2. Politics of Time

The sessions will be held in English without translation.

16:00–21:30

Chair: Alexei Penzin, Ilya Budraitskis

Participants: Michael Heinrich, Jodi Dean, Greg Yudin, Ilya Budraitskis, Artemy Magun, Dimitris Vardoulakis, Keti Chukhrov, Alexey Savin

Participants: Michael Heinrich, Jodi Dean, Greg Yudin, Ilya Budraitskis, Artemy Magun, Dimitris Vardoulakis, Keti Chukhrov, Alexey Savin

Saturday, May 25

11:00-13:30

Chair: Artemy Magun

Participants: Marina Simakova, Andrey Shevchuk, Alexei Penzin, Maurizio Lazzarato

Participants: Marina Simakova, Andrey Shevchuk, Alexei Penzin, Maurizio Lazzarato

14:00-15:00

Russian Association for Political Philosophy: Official Presentation

Participants: Artemy Magun, Greg Yudin

16:00–18:00

Chair: Marina Simakova

Participants: Cinzia Arruzza, Elena Gapova, Angela Dimitrakaki

Participants: Cinzia Arruzza, Elena Gapova, Angela Dimitrakaki

18:30–20:30

Chair: Greg Yudin, Artemy Magun

Participants: Vladimir Mau, Teodor Shanin, Valery Podoroga, Sergey Zuev, Vladislav Sofronov

Participants: Vladimir Mau, Teodor Shanin, Valery Podoroga, Sergey Zuev, Vladislav Sofronov

Session 1. Marx and Contemporary Materialism

In terms of the old divide between materialism and idealism, the contemporary philosophical conjuncture is rather paradoxical. Alain Badiou recently branded as "democratic materialism" the currents of contemporary thought that base themselves on the assumption that "there are only bodies and languages" while excluding the concept of truth as evental and revolutionary process. Badiou argues that this variety of materialism rather supports the ideological discourse of late capitalism. Although the legacy of German Idealism is a vital part of today's discussion, it is unlikely that any current of contemporary thought would declare itself as "idealist" except a poetic or an openly religious phenomenology. Today, we have a Kampfplatz of multiple "new materialisms" and "realisms" rather than a divide between materialism and idealism. However, the underlying antagonism within this field is the same as the division that has always been present in capitalist modernity. The varieties of contemporary materialism can be seen as either being timidly or openly complying with the late-capitalist ideological discourse, or as being rebelliously anti-capitalist. The panel will ask what are those specific division lines in the contemporary struggle of materialisms? What should the strategy be of the materialism that would allow the Marxist tradition reinvent itself in this complex conjuncture? This question seems to be even more complicated since, at different stages of Marx's philosophical formation, the latter had also been reflecting the "idealist" aspects inherited from German classical thought. Additionally, the panel will question if we have to limit ourselves to a "ruthless criticism" of those supposed materialisms which both betray the emancipatory and radical tradition of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and instigate a "speculative" detachment from the toxic pressures of the current political momentum, or can we consider a contemporary materialist approach that admits a materialist "speculation" similar to the late-Soviet philosophical debates on the concept of the "ideal" in the 1970's and 1980's. Finally, from today's viewpoint, how can the post-Soviet and postcolonial conditions contribute not only to the emergence of the "new materialisms", but also to a resurgence of the materialist philosophy that would be faithful to Marx?

The session will be held in English without translation.

Chair:

Alexei Penzin

Participants:

Karen Sarkisov

Maria Chehonadskih

Svenja Bromberg

Andrés Saenz De Sicilia

Armen Aramyan

Stefano Pippa

Anton Syutkin

Chair:

Alexei Penzin

Participants:

Karen Sarkisov

Maria Chehonadskih

Svenja Bromberg

Andrés Saenz De Sicilia

Armen Aramyan

Stefano Pippa

Anton Syutkin

10:30 – 12:30

PART I: CONTEMPORARY MATERIALISMS AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF MARX'S THOUGHT

Karen Sarkisov (V-A-C and Moscow State University) – Fraught Relations: The Faces of Contemporary Materialism

Continental thought has recently seen a veritable proliferation of materialisms and realisms of every kind: new materialism, agential realism, vital materialism, speculative materialism, transcendental materialism, just to name a few. It is telling that Alain Badiou terms today's dominant ideological stance as 'democratic materialism,' to which he opposes his own 'materialist dialectic.' To be sure, many versions of the current materialist inquiry sit neatly in a particular philosophical lineage and can be traced back to one of the leading figures of twentieth-century philosophy (e.g., Deleuze for monistic vital materialism). But is there a reliable criterion that could help provide a general mapping of, and signal a 'primary' contradiction within, this vast theoretical landscape? I would argue that one such criterion might be relationality / nonrelationality. It is true that some of these philosophies are characterized by the privileging of process, assemblages, polymorphism, hybrids, life, embodiment and physicality, patchiness and inconclusiveness, provisional generalizations, situatedness and finitude, mutability and connectionism as well as maintaining the continuity between—and constitutive entanglement of—culture and nature, the human and the non-human, bios and zoe etc.—whereas others are marked by fundamental indifference and favor clear-cut divisions, discontinuity, mutual withdrawals, caesurae, strong distinctions (e.g., between human animal and the Subject) and de-correlation (for example, that of thought and being) as well as a striving for the Absolute (incidentally, the original meaning of the Latin absolvo is to detach). That being said, the described criterion is only an approximation and some theoretical projects positioned on either side of the divide have internal tensions and could not be easily lumped together under one heading.

Maria Chehonadskih (Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London) – Before or After Kant? The Critical and Pre-Critical Foundations of Marxist Materialism

The paper addresses the status of critique in Marxist theory and problematises a current turn to the pre-Kantian and therefore, pre-critical traditions of thought in contemporary philosophy. A break with the post-Kantian promise of critique in the recent philosophical discourses, is the break with a core epistemological ground of Western European Marxist theory – the critique of political economy and the critique of bourgeois society. The pre-critical agenda in philosophy epitomises a shift to the positivity of descriptive ontologies and signifies the abandonment of Marxist project in philosophy all together. The Marxism addresses this pre-critical turn either in terms of the victory of analytical philosophy over the continental tradition or examines it sociologically, as a symptom of the current rise of the far-right tendencies, and the idealism and mysticism corresponding to it. The paper will reassess the pre-critical problematic from the standpoint of a crisis of critique in the contemporary Marxism. It will argue for necessity of a new Marxist ontological enquiry. The case for such enquiry will be made by discussing the pre-critical epistemological foundations of Soviet Marxism and its ontological agenda (a Soviet reassessment of the debates on body-mind dualism and an ontology of organisation).

Svenja Bromberg (Goldsmiths, University of London) – Emancipation, Politics and Materialism after Marx

How to be a materialist when it comes to thinking politics? This question occupied Marxists in the aftermath of '68 and it manifested not just in key publications such as Marx et sa critique de la politique (1979) by Balibar, Luporini and Tosel and Badiou's Peut-en penser la politique (1985) but also in several journal volumes, e.g. of Das Argument or Actuel Marx, being dedicated to Marx's political theory between the mid-1970s up to the early 90s. Unfortunately, the trajectory of this research question has had two in my view unfortunate consequences. On the one hand, within Post-Marxism, the conclusion that Marx's position on politics remained contradictory throughout his writings (see e.g. Balibar) has led to embracing different version of radical democracy as the only reasonable way out, abandoning the link between politics and revolution. On the other hand, demands for renewing the communist idea, as we for example find it in Badiou's work, are embracing an idealist, explicitly philosophical conception of politics that is no longer overly concerned with Marx's lifelong aim of departing from philosophy (as idealist, esp. Hegelian philosophy) and grounding politics and political thought in historical-materialist principles. My aim in this paper is to show that it is by rethinking the concept of emancipation in Marx, which by definition refers to critique (of the existing regimes of exploitation and oppression) and construction (of another, non-bourgeois form of social existence), that we are able to return to the debates around how to think politics in a materialist way. I will outline the value of holding on to the concept within the Marxist tradition, whilst I draw on the various critical readings from the post-'68 moment as well as influences from the so-called new materialisms in order to overcome the limits of Marx's own proposals (and subsequent equally limited interpretations).

Andrés Saenz De Sicilia (Newcastle University) – Materialism and Marx's Concept of Social Objectivity

The 'new' materialist outlook announced in Marx's writings from the mid-1840s onwards has often been understood to signal a break with and devastating attack on 'self-sufficient philosophy'. To whichever extent philosophical motifs persist in Marx's later writings, these are generally held to support his engagement with extra-philosophical concerns (e.g. the critique of political economy). This paper pauses to consider the implications of Marx's materialism for philosophical discourse itself; not in order to reinscribe the materialist gesture within philosophy, but rather to grasp the way in which this gesture has thrown philosophy into crisis, irreversibly expanding the scope of its concerns and methodological self-consciousness. In contrast to contemporary materialisms of a democratic or apologetic bent Marx's approach is distinguished by its problematisation of the autonomy of thought, insisting on the circumscription of speculation vis-à-vis its historical, social and practical conditions. At the level of philosophical discourse this difference is manifested most fundamentally in terms of competing conceptions of objectivity, or of the constitution of the real. This paper therefore asks: what kind of ontology is proposed in Marx's materialism? What 'actuality' does it obey or sanction? To answer these questions, I draw on and develop the conception of social objectivity (in contrast to an ideal or physical objectivity) present in Marx's project. This concept enables us to trace Marx's overcoming of the opposition between idealism (in its contemporary guises: unbound rationalism, speculation and constructivism) and 'traditional' materialism (as physicalism, naturalism or vitalism) in order to construct a genuinely critical materialism today.

12:30– 13:00

BREAK

13:00 – 15:00

Part II: Aspects and Critiques of the Current Debates on Materialism

Armen Aramyan (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences) – Fetish of Materialism, Materiality of Fetishism: Towards a Materialist Critique of Ideology

All various traditions of Marxist critique of capitalist/bourgeois culture may be traced back to the Marxian notion of 'commodity fetishism'. The capitalist culture is portrayed as producing alienated meanings embodied in hollow objects and/or images. Colonial roots of the notion of 'fetishism' stand out in the plain sight: first presented as a coherent notion in the work of 18th century French historian Charles de Brosses in order to denote the primitivity of all non-monotheist religious beliefs, it then had an extensive history of usage in evolutionist narratives of 19th century social/historical science (Comte, Tylor, Arnold), which were substantial for defining 'society'/'culture' as an object of scientific endeavor. As usual, Marx turns this interpretative tradition 'upside down', and reveals the irony: a colonizer her/himself is a true fetishist with his feitiço being money, gold, commodity, and these false gods are powerful enough to drive the colonizer to the shores of West Africa. In spite of the turn, Marxist critique of capitalism faces here with some difficulties in terms of its' claimed materialism: on the one hand, it is a materialist critique of an abstract force, which alienates things from their meanings (e.g. commodities from their use-values), on the other hand – a critique of materiality embodied in a ('fake') mulitiplicity of commodities and things: a critique of abstraction and a critique of concreteness. In the presentation I will trace the roots of 'critique of fetishism' tradition from thinkers of the Enlightenment, to various strains of Marxist critique of capitalist culture and ideology (incl. critique of 'postmodern' society). This will allow me to present a prospect of a materialist (counter-)notion of 'ideology' with roots in post-structuralist philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari.

Stefano Pippa (University of Milano-Bicocca) – Thinking the fait à accomplir. Althursser's Contribution to Current Debates on Materialism

One of Althusser's most important and abiding preoccupations was, as is well-known, the construction of a definition of materialist philosophy. Such a task, that Althusser set himself in the sixties, underwent several shifts, the most famous of which is the one from the idea of a Marxist philosophy understood as a 'Theory of theoretical practices' (For Marx, 1965 and Reading Capital, 1965) to the idea of philosophy as 'class struggle in theory' (Lenin and Philosophy, 1968). However, this paper is going to argue for the relevance for today's debates on materialism of a third and still underrated (or totally ignored) definition of materialist philosophy in Althusser, which he called in some notes from the seventies "philosophy of the fait à accomplir". I will argue that such a redefinition of materialist philosophy represents a major and fertile attempt to rethink the relationship between philosophy, materialism and politics insofar as it articulates in an original way ontology, critique and transformation of the 'current conjuncture'. Placing this redefinition of philosophy under the specific injunction of Marx's 11th thesis on Feuerbach, the paper 1) will extract Althusser's redefinition of materialist philosophy through a reading of his engagement with Machiavelli, and 2) will argue that such a definition paves the way for a re-conceptualisation of materialist philosophy not as a specific set of theses about being (the old alternative being/thought which is still operational behind much of the contemporary debate on materialism(s)), but a specific 'attitude of thought to objectivity' which produces material effects.

Anton Syutkin (European University at Saint Petersburg) – Rethinking the Absolute in Contemporary Materialist Dialectics

The contemporary dispute between the materialists from the point of view of the 11th thesis of Marx on Feuerbach is a dispute between the new "old materialism" and the old "new materialism". The new "old materialism", which only explains, but does not transform the world, includes all panpsychist and eliminativist philosophies, united under the title of "speculative realism". All these philosophies become politically powerless, since they do not create the theory of the subject, replacing it with meditations about the hyper-chaos, the allure between autonomous objects, the productive force of nature and the insignificance of existence in the light of the coming solar catastrophe.

Contemporary materialist dialectics, therefore, takes the place of the old "new materialism". Adrian Johnston, the leading researcher of this philosophical movement, considers Alain Badiou and Slavoj Zizek as materialist theorists of the subjectivity. They both insist on the existence of contradictions in the material substance, which leads to the emergence of an immaterial subject. Thus, the role of substance in the materialist dialectic is reduced, firstly, to the background on which the subject arises, and, secondly, to the internal obstacle preventing the subject from gaining idealist autonomy. Such an interpretation of materialist dialectics politically leads to the identification of communism with voluntarist party politics, even if it is reflexively aware of its own limits.

Contrary to Johnston, I think that contemporary materialist dialectics is the theory of the absolute, in which the substance's contradictions are reconciled through subjective mediation. In the case of Alain Badiou the absolute is the truth process, which is the subjective localization of the void in concrete situation, and in the case of Slavoj Zizek it is the death-drive after subjective return to it. However, in order to release the politics of contemporary materialist dialectics from a voluntarist (and, therefore, anti-democratic) deviation, it is necessary to pay attention also to the legacy of the late Soviet materialist dialectics of Mikhail Lifshits, which links communism with the revolutionary-democratic tradition.

Contemporary materialist dialectics, therefore, takes the place of the old "new materialism". Adrian Johnston, the leading researcher of this philosophical movement, considers Alain Badiou and Slavoj Zizek as materialist theorists of the subjectivity. They both insist on the existence of contradictions in the material substance, which leads to the emergence of an immaterial subject. Thus, the role of substance in the materialist dialectic is reduced, firstly, to the background on which the subject arises, and, secondly, to the internal obstacle preventing the subject from gaining idealist autonomy. Such an interpretation of materialist dialectics politically leads to the identification of communism with voluntarist party politics, even if it is reflexively aware of its own limits.

Contrary to Johnston, I think that contemporary materialist dialectics is the theory of the absolute, in which the substance's contradictions are reconciled through subjective mediation. In the case of Alain Badiou the absolute is the truth process, which is the subjective localization of the void in concrete situation, and in the case of Slavoj Zizek it is the death-drive after subjective return to it. However, in order to release the politics of contemporary materialist dialectics from a voluntarist (and, therefore, anti-democratic) deviation, it is necessary to pay attention also to the legacy of the late Soviet materialist dialectics of Mikhail Lifshits, which links communism with the revolutionary-democratic tradition.

Session 2. Politics of Time

One of the most widespread criticisms mounted against Marx over the past century is related to his endorsement of the idea of linear progress. As a matter of fact, Marx's historical optimism was closely linked to the universal characteristic of capital of its incessant expansion, where "all that is solid melts into air", including pre-capitalist relations. Thus, the progressive effect of the destructive work of capital provides a historical justification for capital itself, while rendering anything that does not fit into its totality insignificant. Yet, various thinkers, from Althusser and Bloch to world-system and postcolonial theorists, oppose such a progressivist (and deterministic) understanding of Marx. Instead, they insist on the historical specificity of capitalism and its destructive effect (and hence, its dialectical sublation) which does not inevitably culminate in a social alternative. Benjamin's critique of "homogeneous empty time", intrinsic to historical progress, is crucial to this approach. In contrast, it offers a vision of contemporaneity that allows for temporal non-simultaneity and incorporates all of the "survivals" of the pre-capitalist past — albeit alien to market rationality — into its complex structure. At the same time, this "melancholic" tendency that has in many ways defined Marxism in past decades has been vehemently criticized by the "left accelerationists" who wish to revive the Marxist belief in the limited development of capitalist relations, which is seen as a necessary precondition for capitalism to be overcome. In this sense, can we say (following Wallerstein) that there are "two Marxs" — progressivist and anti-progressivist — who oppose each other within the Marxist tradition? Could ''melancholic" Marxism be conducive to the understanding of current political phenomena (i.e., right-wing populism and the renaissance of conservative ''archeopolitics''), and, if so, in what way? Or, could the return to the progressivist perspective help us reveal the emancipatory potential of the increasingly rapid development of technologies?

The session will be held in English without translation.

Chair:

Ilya Budraitskis

Participants:

Gregor Shafer

Roberto Mozzachiodi

Adam Leeds

Ilya Konovalov

Zakhar Popovych

Jason Goldfarb

Chair:

Ilya Budraitskis

Participants:

Gregor Shafer

Roberto Mozzachiodi

Adam Leeds

Ilya Konovalov

Zakhar Popovych

Jason Goldfarb

10:30 – 12:30

Part I: Towards a history of the Non-linear Time

Gregor Shafer (University of Basel) – "The time is out of joint": On Kairos as the Time of Emancipation

In his study on Lenin of 1924, Lukács states that the essence of Marxism lies in the ability to grasp the right political moment: to think and act within a constellation Lukács refers to as concrete actuality. Lukács resumes this essence by Shakespeare's verse "The readiness is all" – uttered by Hamlet, not by chance, in a time "out of joint".

Grasping the right moment – in classical terminology: the kairós (καιρός) – is a problem of immediate political interest. Every emancipatory politics is confronted with the question of how to get to know when – at what precise moment – the decision to act has to be taken. As Lenin states, missing the right moment could postpone the actuality of the revolution for centuries, making it disappear for generations to come. The decision at the right moment cannot be reduced to a (seemingly) objective-scientific, deterministic scheme of laws (as typical for the Marxism of the II. International), but constitutively bursts any linear concept of – chronological – progress. It rather enacts the courageous choice of a jump into the void of an interstice – a gap, a lacuna, a radical discontinuity between the times, the constitutively revolutionary conjuncture of a "time out of joint"; and it is only by this performative act that a revolutionary subject can be constituted. As Benjamin's critique of a concept of linear progress, but also Badiou's and Agamben's readings of Saint Paul make it clear, this revolutionary subjectivity is an integral part of thinking the kairós against the background – as well – of its political-theological origin in figures of Christian messianism. Far from being a random coup d'état, the respective kairós connects the singularity of a specific conjuncture with a philosophical, nay metaphysical claim to universal truth. What, insofar, can be understood as progress, is a narrative of emancipatory truth constituted by the constellation of – multiple – singular emancipatory moments and specific sequences. The hereby involved transhistorical temporality does not derive from the framework of a "neutral" chronological time, but is connected with the very immanent perspective of the subjects participating in the process of emancipation – and constituted by their ongoing work.

It is the aim of the present paper to outline the hereby sketched concept of kairology in the Marxist tradition and to argue for its actuality.

Grasping the right moment – in classical terminology: the kairós (καιρός) – is a problem of immediate political interest. Every emancipatory politics is confronted with the question of how to get to know when – at what precise moment – the decision to act has to be taken. As Lenin states, missing the right moment could postpone the actuality of the revolution for centuries, making it disappear for generations to come. The decision at the right moment cannot be reduced to a (seemingly) objective-scientific, deterministic scheme of laws (as typical for the Marxism of the II. International), but constitutively bursts any linear concept of – chronological – progress. It rather enacts the courageous choice of a jump into the void of an interstice – a gap, a lacuna, a radical discontinuity between the times, the constitutively revolutionary conjuncture of a "time out of joint"; and it is only by this performative act that a revolutionary subject can be constituted. As Benjamin's critique of a concept of linear progress, but also Badiou's and Agamben's readings of Saint Paul make it clear, this revolutionary subjectivity is an integral part of thinking the kairós against the background – as well – of its political-theological origin in figures of Christian messianism. Far from being a random coup d'état, the respective kairós connects the singularity of a specific conjuncture with a philosophical, nay metaphysical claim to universal truth. What, insofar, can be understood as progress, is a narrative of emancipatory truth constituted by the constellation of – multiple – singular emancipatory moments and specific sequences. The hereby involved transhistorical temporality does not derive from the framework of a "neutral" chronological time, but is connected with the very immanent perspective of the subjects participating in the process of emancipation – and constituted by their ongoing work.

It is the aim of the present paper to outline the hereby sketched concept of kairology in the Marxist tradition and to argue for its actuality.

Roberto Mozzachiodi (Glodsmiths College, University of London) – Non-Linear Marxisms in Post-War France

At distinct moments of crisis for the Marxist political and/or theoretical project, Henri Lefebvre, Louis Althusser and Jacques Derrida, who were variously proximate to the French Communist Party, all contributed re-interpretations of the place of philosophy in Marxism as an attempt to guard against the ossification of Marxist theory and practice. In each of their efforts to do so, they aligned with Marx a definitively non-linear approach to historical development, which had ramifications on how they conceived revolutionary theory and politics.

In his 1956 text La penseé de Lénine, Lefebvre drew a theoretical genealogy between the 1857 Introduction of the Grundrisse and Lenin's economic writing to circumscribe a consistent historical outlook which centred developmental unevenness. Lefebvre linked the emergence of uneven development in terms of a radical critical method specific to Marxism which took the negation of all philosophical systematicity as its point of departure.

In his 1969 text Lenin Before Hegel, Althusser reached the conclusion in surveying Lenin's materialist reading of Hegel's Logic, that "history is a process without a subject", a formulation which consolidated the underlying anti-teleological bent of his earlier Contradiction and Overdetermination and looked forward to quasi anti-dialectical thrust of his aleatory materialism.

In Derrida's 1993 Specters of Marx, he gave expression to a political theology by way of a critique of the aporias of Marx's revolutionary prescriptions. What Derrida called "messianicity without messianism" was an attempt to reckon with the inheritance of Marx without recourse to a soft Hegelian telos. With particular attention paid to the 11th Thesis on Feuerbach, Derrida identifies the disjuncture of a textual injunction which aspired to transform the structure of the theory/practice opposition, an aspiration which short-circuited the temporality of ethico-political agency.

In this paper, I will elaborate the theoretical specificities of these non-linear Marxisms and the political and theoretical crises which engendered them.

In his 1956 text La penseé de Lénine, Lefebvre drew a theoretical genealogy between the 1857 Introduction of the Grundrisse and Lenin's economic writing to circumscribe a consistent historical outlook which centred developmental unevenness. Lefebvre linked the emergence of uneven development in terms of a radical critical method specific to Marxism which took the negation of all philosophical systematicity as its point of departure.

In his 1969 text Lenin Before Hegel, Althusser reached the conclusion in surveying Lenin's materialist reading of Hegel's Logic, that "history is a process without a subject", a formulation which consolidated the underlying anti-teleological bent of his earlier Contradiction and Overdetermination and looked forward to quasi anti-dialectical thrust of his aleatory materialism.

In Derrida's 1993 Specters of Marx, he gave expression to a political theology by way of a critique of the aporias of Marx's revolutionary prescriptions. What Derrida called "messianicity without messianism" was an attempt to reckon with the inheritance of Marx without recourse to a soft Hegelian telos. With particular attention paid to the 11th Thesis on Feuerbach, Derrida identifies the disjuncture of a textual injunction which aspired to transform the structure of the theory/practice opposition, an aspiration which short-circuited the temporality of ethico-political agency.

In this paper, I will elaborate the theoretical specificities of these non-linear Marxisms and the political and theoretical crises which engendered them.

Adam Leeds (Columbia University) – The lowest stage of socialism: The republic, the factory, and history in the Marxism of the Second International

This paper argues that around the end of the nineteenth century the understanding of socialism in the Marxist tradition underwent a mostly unnoticed transformation. During this period an understanding of socialism as a form of radicalized republicanism, a republicanism extended to the workplace, was gradually eclipsed by an understanding of socialism derived from the forms of corporate capitalism. The new understanding of socialism was derived from the theory of imperialism of the German Social Democrats, constituting its domestic face. I claim that this theory was the reflection within Marxism of changes in capitalism itself, of what is sometimes called the "Second Industrial Revolution." The new understanding of socialism as the general cartel in the hands of the worker's state—i.e., an industrial state form—is what underlay the institutional formation of the Soviet Union.

The progressivist temporality of Second International Marxism, its stagist historicism, required projecting the present-day forms of capitalism into the future forms of socialism. This paper aims to elucidate both understandings of socialism, explain why the later grew at the expense of the earlier, and show how they coexisted in thought of the Bolsheviks.

The progressivist temporality of Second International Marxism, its stagist historicism, required projecting the present-day forms of capitalism into the future forms of socialism. This paper aims to elucidate both understandings of socialism, explain why the later grew at the expense of the earlier, and show how they coexisted in thought of the Bolsheviks.

12:30 – 13:00

BREAK

13:00 – 15:00

Part II: Cognitive capitalism and the plurality of futures

Ilya Konovalov (Higher School of Economics, Moscow) – On the notion of abstract time

Abstract time is one of the most important notions that features in the discussion of capitalist time regime. Supposedly, capitalist relations create a basis for expanding of the specific form of time, which marginalizes lived experience and multiple temporalities in favour of linear profit-oriented clock time. While usual way for pointing to the inadequacy of this notion, is to demonstrate that capitalism has never really erased multiple temporalities and even dependent on its existence, I will problematize notion "abstract time" not from the side of lived and concrete, but from the side of its genesis in the notion of "abstract labour".

While "abstract labour" has many different understandings (a form of activity, a form of representation, form social relations etc.) and is a part of the complex web of notions (labour-value-commodity-price), "abstract time" is often reduced to self-evident representation materialized in clocks and calendars. Moreover, the meaning of "abstract labour" and its place in the theoretical edifice of Marx remains the hotly debated, whereas "abstract time" appears to be a suspicious point of consensus.

I will review the history of conceptualisation of "abstract time" from early intuitions (Lukács, Benjamin), through later unorthodox readings of Marx (Heinrich, Arthur, Postone) and political readings of Marx (post-operaism, open Marxism) to the contemporary works (Lotz, Pitts).This theoretical genealogy will allow me to show that different understanding of abstract labour has different, but frequently neglected implications for the conceptualization of abstract time. It should help us to understand whether "abstract time" really gives way to notions such as digital time, network time, real-time, which are more adequate to the "cognitive capitalism" and "new economy". To conclude, I will point out that dominant and self-evident understanding of abstract time is putting an obstacle on our way imagining alternative collective times, leaving us with the only alternative of concrete unmediated activity of an individual.

While "abstract labour" has many different understandings (a form of activity, a form of representation, form social relations etc.) and is a part of the complex web of notions (labour-value-commodity-price), "abstract time" is often reduced to self-evident representation materialized in clocks and calendars. Moreover, the meaning of "abstract labour" and its place in the theoretical edifice of Marx remains the hotly debated, whereas "abstract time" appears to be a suspicious point of consensus.

I will review the history of conceptualisation of "abstract time" from early intuitions (Lukács, Benjamin), through later unorthodox readings of Marx (Heinrich, Arthur, Postone) and political readings of Marx (post-operaism, open Marxism) to the contemporary works (Lotz, Pitts).This theoretical genealogy will allow me to show that different understanding of abstract labour has different, but frequently neglected implications for the conceptualization of abstract time. It should help us to understand whether "abstract time" really gives way to notions such as digital time, network time, real-time, which are more adequate to the "cognitive capitalism" and "new economy". To conclude, I will point out that dominant and self-evident understanding of abstract time is putting an obstacle on our way imagining alternative collective times, leaving us with the only alternative of concrete unmediated activity of an individual.

Zakhar Popovych (Dobrov STEPs center NAS of Ukraine) – Whether progress? Towards universal exchange and total communization of knowledge

In the second half of the 20th century, Marxism was attacked for its alleged Eurocentric universalism, which in particular manifested itself through the notion of progress that Marx attributed to capitalism in his early writings, as well as inevitability of the same sequence of formations that all societies would pass before reaching the final structural conflict. However, the analysis of his later and little-known texts testifies his conceptual shift from the unilinear view on history. As other writers also mentioned, in pre-capitalist societies, capitalism "puts itself onto" the existing system of relations and erodes it without providing them with the virtues of political emancipation that succeeded in the capitalist centers. At the front-line of capitalist expansion the societies find themselves in a historical impasse in the absence of progressive forms to be forged from the ruins of the old ones.

It's essential thus to conceive of capitalism not as a system where various societal configurations merely coexist, but the single capitalist "organism", the development and decay of different parts of which is an interdependent process. Exploitation and accumulation are seen here as the illness, which results in the dispossession and oppression of one societies by the other. The more this illness progresses, the more inequality it yields. In turn, to understand capitalist development as a set of more or less self-reliant processes (modernization theory) means to defend neoliberal conceptualization of capitalism and to obscure its dead-end, which explicitly manifests itself in the periphery of the system.

Analysis of the historical specificity of colonial practices tends to be dominated by the analysis of colonial discourse. While capitalism causes and creates a favorable environment for the spread of colonial discourse - through economic oppression and global inequality - it appropriates the tools of political correctness and thus whitewashes the centers of capitalist hegemony.

The contemporary system of progressing poverty and monopolisation of intellectual property right etc. questions the very possibility of progress under capitalism. As Marx put it: "Once the narrow bourgeois form has been peeled away, what is wealth other than the universality of individual needs, capacities, pleasures, productive forces etc., created through universal exchange?" (Grundrisse) Whether general intellect, creativity and knowledge sharing can be legitimized as a universalizing principle of the progress?

It's essential thus to conceive of capitalism not as a system where various societal configurations merely coexist, but the single capitalist "organism", the development and decay of different parts of which is an interdependent process. Exploitation and accumulation are seen here as the illness, which results in the dispossession and oppression of one societies by the other. The more this illness progresses, the more inequality it yields. In turn, to understand capitalist development as a set of more or less self-reliant processes (modernization theory) means to defend neoliberal conceptualization of capitalism and to obscure its dead-end, which explicitly manifests itself in the periphery of the system.

Analysis of the historical specificity of colonial practices tends to be dominated by the analysis of colonial discourse. While capitalism causes and creates a favorable environment for the spread of colonial discourse - through economic oppression and global inequality - it appropriates the tools of political correctness and thus whitewashes the centers of capitalist hegemony.

The contemporary system of progressing poverty and monopolisation of intellectual property right etc. questions the very possibility of progress under capitalism. As Marx put it: "Once the narrow bourgeois form has been peeled away, what is wealth other than the universality of individual needs, capacities, pleasures, productive forces etc., created through universal exchange?" (Grundrisse) Whether general intellect, creativity and knowledge sharing can be legitimized as a universalizing principle of the progress?

Jason Goldfarb (Duke University) – Speculative Marxism: On the (Im)Possibility of the Future

Several contemporary Marxist theorists—Fredric Jameson, Slavoj Žižek, and Mark Fisher among others—have argued that the progressivist or teleological reading of Marx is no longer plausible. The claim is that with the arrival of "late capitalism", or the advancement of formal and real subsumption, the possibility of imagining a post-capitalist world, let alone its inevitability, is foreclosed. In an era of "capitalist realism" it seems more likely that any contradiction between the forces and relations of production will lead to a further exacerbation of crisis rather than any sort of sublation (aufhebung). In analytic terms, the "fettering thesis," last defended by G.A. Cohen, seems dated. This all poses an obvious difficulty for those interested in speculative and post-capitalist politics: what can be the role of the future and speculative imagination when both are barred? Is "despair" the only option? Drawing on the work of Hegelian-Marxism, this paper responds in a dialectical manner: agreeing with Fisher and others, it (1) rejects Marxist progressivism, yet (2) argues that such a rejection is the condition for, not the limitation of, a post-capitalist future.

The "melancholy Marx" is the radical Marx. The value of speculation therefore lies not in the capacity to think alternative worlds, but in extrapolating from the present world, thereby demonstrating its limits. The perpetual attempt to think the "new" in fact reinforces capital, providing fertile ground for capitalist commodification. Once we reject this attempt, fully accepting the fatalism of our epoch, authentic futural-temporal possibilities appear.

The "melancholy Marx" is the radical Marx. The value of speculation therefore lies not in the capacity to think alternative worlds, but in extrapolating from the present world, thereby demonstrating its limits. The perpetual attempt to think the "new" in fact reinforces capital, providing fertile ground for capitalist commodification. Once we reject this attempt, fully accepting the fatalism of our epoch, authentic futural-temporal possibilities appear.

Plenary Session 1. State – Democracy – Communism

Even though Marx didn't provide a systematic theory of the state, the place of the state in capitalism is one of the main topics the scholars of today inherit from his legacy. The future of the state is now obscure: while there are strong expectations that we will soon witness it disappearing, many concerns are also raised about the unprecedented power that states enjoy over human lives. After the fall of the Soviet "real socialism" Marx is regarded by some as a prophet of a radical democracy, while many theorists attempt to renew and redefine the communist imaginary (on which Marx himself did not sufficiently elaborate). The conflict between representative democracy and communist negation of representation as a form of alienation keeps reemerging in post-Marxist thought.

Is the contemporary state merely an executive committee of the ruling class, or does it raise itself "above its particular elements"? What is role of states in reproduction of capital and society? Does Marxian critique of bourgeois democracy invalidate any kind of democratic project? And what is the prospect to revive the communist aspirations in politics? And finally, should we expect the state withering away?

Is the contemporary state merely an executive committee of the ruling class, or does it raise itself "above its particular elements"? What is role of states in reproduction of capital and society? Does Marxian critique of bourgeois democracy invalidate any kind of democratic project? And what is the prospect to revive the communist aspirations in politics? And finally, should we expect the state withering away?

Chair:

Alexei Penzin

Ilya Budraitskis

Participants:

Michael Heinrich

Jodi Dean

Greg Yudin

Ilya Budraitskis

Artemy Magun

Dimitris Vardoulakis

Keti Chukhrov

Alexey Savin

Alexei Penzin

Ilya Budraitskis

Participants:

Michael Heinrich

Jodi Dean

Greg Yudin

Ilya Budraitskis

Artemy Magun

Dimitris Vardoulakis

Keti Chukhrov

Alexey Savin

16:00 – 18:30

PART 1

Chair: Alexei Penzin

Chair: Alexei Penzin

Michael Heinrich (Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft, Berlin) – Marx's Hidden Theory of the State and the Contemporary State of the Real Existing States

Jodi Dean (Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York) – Communism or Neo-Feudalism?

Greg Yudin (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences) – Democracy as a Mystery of All Constitutions: The Problem of Bonapartism

Ilya Budraitskis (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences) – Satan Drives out Satan: Proletarian State as a Political and Moral Problem

Discussion

Jodi Dean (Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York) – Communism or Neo-Feudalism?

Greg Yudin (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences) – Democracy as a Mystery of All Constitutions: The Problem of Bonapartism

Ilya Budraitskis (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences) – Satan Drives out Satan: Proletarian State as a Political and Moral Problem

Discussion

18:30 – 19:00

COFFEE-BREAK

19:00 – 21:30

PART 2

Chair: Ilya Budraitskis

Chair: Ilya Budraitskis

Artemy Magun (European University at Saint Petersburg) – Thinking the Communist State

Dimitris Vardoulakis (Western Sydney University) – Genealogy of Materialism and the State

Keti Chukhrov (Higher School of Economics, Moscow; Marie Sklodowska Curie fellow, University of Wolverhampton (UK)) – Capitalist Unconscious in the Communist Imaginaries

Alexey Savin (Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration) – State, Dialectics, and Gattungswesen

Discussion

Dimitris Vardoulakis (Western Sydney University) – Genealogy of Materialism and the State

Keti Chukhrov (Higher School of Economics, Moscow; Marie Sklodowska Curie fellow, University of Wolverhampton (UK)) – Capitalist Unconscious in the Communist Imaginaries

Alexey Savin (Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration) – State, Dialectics, and Gattungswesen

Discussion

Plenary Session 2. Capitalism – Money – Labor

Analysis and critique of the capitalist system have always been the hallmarks of the Marxist thought, even though Marx did not invent the term 'capitalism' himself. However, the unfolding of neoliberal capitalism encourages challenging some Marxist dogmas with Marx's concepts. Radical transformations of work over two last centuries have not removed the duality of labor and capital and its inherent contradictions but made some theorists revive Marx's concept of General Intellect and his project of overcoming of work as such. The emergence of debt as key mechanism of social reproduction pushes towards reconsidering the classic analysis of money-commodity interfaces in capitalist economy. At the same time, the number of proletarians and labor migrants in the world is constantly growing, exacerbating the global asymmetries and inequalities. New technologies and machines seem to increase the labor time, rather than diminish it.

Is there a hope for a future without work and what is the way to gain it? What are the new forms of cooperation opposing the new forms of exploitation? And does the critique of capitalism constitute a viable political strategy in the age of conservative reaction?

Is there a hope for a future without work and what is the way to gain it? What are the new forms of cooperation opposing the new forms of exploitation? And does the critique of capitalism constitute a viable political strategy in the age of conservative reaction?

Chair:

Artemy Magun

Participants:

Marina Simakova

Andrey Shevchuk

Alexei Penzin

Maurizio Lazzarato

Artemy Magun

Participants:

Marina Simakova

Andrey Shevchuk

Alexei Penzin

Maurizio Lazzarato

11:00 – 13:30

Chair: Artemy Magun

Marina Simakova (European University at Saint Petersburg) – Marxism in Reactionary Times

Andrey Shevchuk (Higher School of Economics, Moscow) – Understanding Work in the Gig Economy

Alexei Penzin (University of Wolverhampton (UK); Institute of Philosophy RAS, Moscow) – Workdays without End. Towards the Genealogy of "Always-On" Capitalism

Maurizio Lazzarato (Pantheon-Sorbonne University, University Paris I) – Money, debt and war

Discussion

Andrey Shevchuk (Higher School of Economics, Moscow) – Understanding Work in the Gig Economy

Alexei Penzin (University of Wolverhampton (UK); Institute of Philosophy RAS, Moscow) – Workdays without End. Towards the Genealogy of "Always-On" Capitalism

Maurizio Lazzarato (Pantheon-Sorbonne University, University Paris I) – Money, debt and war

Discussion

Plenary Session 3. Feminism – Social Reproduction

The 20th century was marked by manifold victories won by women in their struggles against patriarchy and for gender equality, be they civil, political or social. Many of these accomplishments were made possible by theorists and militants inspired by Marxist thought. Fighting gender discrimination and feminization of poverty, rethinking the family and social reproduction have all become parts of the global feminist agenda. In our era, we have been witnessing large-scale protests against sexism and violence against women. Why, despite all the achievements of the previous generations of feminist theory and political praxis, does gender equality remain elusive? How does productive and reproductive labor, including unpaid domestic work, function in contemporary capitalism? How will gender roles continue to change due to social and technological progress?

Chair:

Marina Simakova

Participants:

Cinzia Arruzza

Elena Gapova

Angela Dimitrakaki

Marina Simakova

Participants:

Cinzia Arruzza

Elena Gapova

Angela Dimitrakaki

16:00 – 18:00

Chair: Marina Simakova

Cinzia Arruzza (New School, New York) – Social Reproduction, Class Formation, and the New Feminist Wave

Elena Gapova (Western Michigan University) – Redistribution and Recognition After Socialism: in Praise of Labour Feminism

Angela Dimitrakaki (University of Edinburgh) – Social Reproduction Imaginaries: The Technology Question

Discussion

Elena Gapova (Western Michigan University) – Redistribution and Recognition After Socialism: in Praise of Labour Feminism

Angela Dimitrakaki (University of Edinburgh) – Social Reproduction Imaginaries: The Technology Question

Discussion

Final Roundtable. How to Look into the Future? A View from Russian Perspective

In much of contemporary political language, there is a global lack of the models for the future, on the one hand, and multiple attempts to predict and foresight the future, on the other. Marx was not a utopian thinker, but he insisted on learning how to see the germs of future in the present: communism was not a utopia but "the real historical movement which abolishes the present state of things". The dogmatic fraction of the Soviet Marxism relied on iron theory of universal successive formations to generate the image of future. However, Marx's own method by no means implied subsuming all diversity of global historical forms under the universal evolution of the forces of production. The Marxist tradition has generated a number of catastrophic scenarios and imaginative projects. What does Marxian view of history grasp in our own present? How does Soviet experience and Soviet Marxist thought help in envisioning the future? What kind of political analysis, action, and creativity can overcome the "paralysis of political imagination" today?

Chairs:

Greg Yudin

Artemy Magun

Спикеры:

Vladimir Mau

Teodor Shanin

Valery Podoroga

Sergey Zuev

Vladislav Sofronov

Greg Yudin

Artemy Magun

Спикеры:

Vladimir Mau

Teodor Shanin

Valery Podoroga

Sergey Zuev

Vladislav Sofronov

ORGANIZERS

Conference is organized by Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences with Institute for Social Sciences RANEPA.

Organizing Committee:

Greg Yudin (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences)

Artemy Magun (European University in Saint-Petersburg)

Marina Simakova (European University in Saint-Petersburg)

Alexei Penzin (University of Wolverhampton)

Ilya Budraitskis (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences)

Local Organizing Committee: Greg Yudin, Marina Pugacheva, Alexandra Zapolskaya, Armen Aramyan, Ilya Budraitskis.

Organizing Committee:

Greg Yudin (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences)

Artemy Magun (European University in Saint-Petersburg)

Marina Simakova (European University in Saint-Petersburg)

Alexei Penzin (University of Wolverhampton)

Ilya Budraitskis (Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences)

Local Organizing Committee: Greg Yudin, Marina Pugacheva, Alexandra Zapolskaya, Armen Aramyan, Ilya Budraitskis.

Contacts:

marx@universitas.ru

The web-site is made by Armen Aramyan and Nastya Podorozhnya (DOXA).

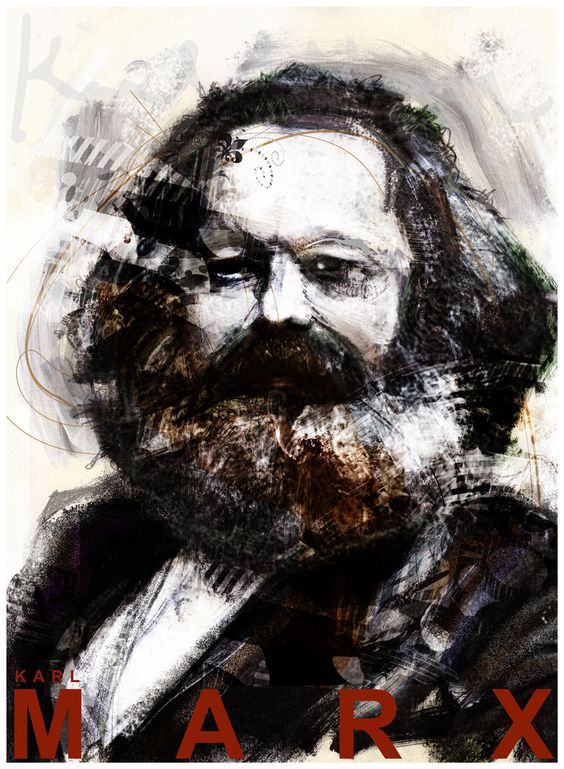

Illustrations by Martin Rowson, Tulio Fagim

Illustrations by Martin Rowson, Tulio Fagim